I previously sung the praises of Japan’s ingenuity in the bathroom, but now I’d like to turn to a part of the home where the Japanese designers and builders still have something learn from their Western counterparts….

An Ingrained Response

Western designers have long admired Japanese vernacular architecture for its flexibility and openness. Paper shoji screens offered the flexibility to re-partition interior spaces, even sliding open to connect the inside of the home to its garden. This provided natural illumination and excellent ventilation, but practically no insulation. Before kerosene oil was imported from the West, the Japanese kept warm by sitting around charcoal braziers (or hibachi) or underneath heavy futon blankets.

Western building styles have now supplanted traditional construction, but the Japanese mindset has not changed as radically with regard to heating and insulating the home. Glass may have replaced paper, but a personal, rather than environmental approach to heating still prevails. Many homes are even sold or rented without heating installed. Portable kerosene heaters are still common — the smell of which takes some getting used to. Users are even instructed to keep a window open to help ventilate the toxic fumes! There is also the kotatsu, a low table with an electrical heating element beneath to keep seated lower bodies snug beneath the surrounding blanket. Plug-in electric carpets are common, as are heated toilet seats! As ingenious as all of this may sound, the amount of energy wasted by such devices is alarming and evidences a widespread lack of energy consciousness.

New Technology – Old Mindset

Exterior insulation is only a recent innovation in residential construction, and single-glazed windows and doors are still common in new homes. Japanese building regulations show a strong concern for ventilation due to humidity and toxic fumes given off by kerosene heaters and off-gassed by synthetic building products. While proper ventilation is necessary, the idea of sealing the building envelope to prevent energy loss is still foreign. Likewise, cold bridging is a common problem, where metal or concrete breach the insulation barrier between interior and exterior causing condensation and energy loss. Whilst energy standards for new homes in Japan exist, they are not upheld by mandatory inspections like there are for fire and structural integrity. Given Japan’s predilection for demolishing homes after a mere 20-30 years, it is easy to see why investment in construction quality remains low. Most home builders compete on cost while maximizing profits by adhering to the lowest acceptable standards.

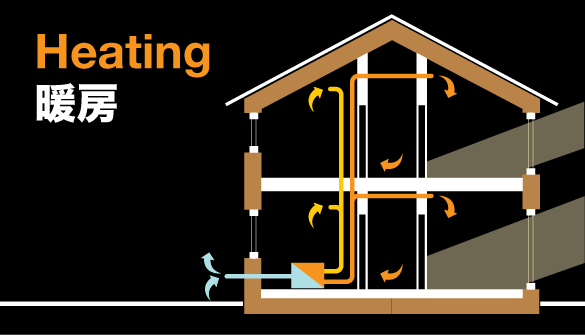

In most modern Japanese homes, each room is heated and cooled by its own wall-mounted air conditioning unit. Heating one room at a time may seem sensible, until one considers that the interior walls are unlikely to be insulated. A great deal of heat energy is wastefully dissipated into unheated rooms, requiring more energy input to maintain comfort. This is not to mention the uncomfortable shock the body feels when going from a warm room into a freezing cold toilet, bathroom, or bedroom.

Passive Solution

The”eco” movement has reached Japan, but sustainable building innovation here seems to fixate on technological solutions. The big Japanese electronics companies (some of whom are also in the home-building business) frame “eco” building in terms of better electrical appliances, fuel cells, and solar power. While these are positive developments, they represent a bolt-on approach. The most significant impact could be made by adopting simple passive design and construction.

The Passive House standard which originated in Germany, has been adopted throughout the rest of the world (including, recently, a handful of projects throughout Japan). The most remarkable aspect of these homes is that a comfortable interior climate can be maintained without active heating and cooling systems. Sunlight and occupants bodies are the main sources of heat energy which is retained by a highly-insulated, air-tight envelope. A heat-exchanger replenishes fresh whilst capturing energy from the exhausted air.

The basic features of a passive house are as follows:

- Compact form and good insulation: All components of the exterior shell of the house are insulated to achieve a U-factor that does not exceed 0.15 W/(m²K) (0.026 Btu/h/ft²/°F).

- Southern orientation and shade considerations: Passive use of solar energy is a significant factor in passive house design.

- Energy-efficient window glazing and frames: Windows (glazing and frames, combined) should have U-factors not exceeding 0.80 W/(m²K) (0.14 Btu/h/ft²/°F), with solar heat-gain coefficients around 50%.

- Building envelope air-tightness: Air leakage through unsealed joints must be less than 0.6 times the house volume per hour.

- Passive preheating of fresh air: Fresh air may be brought into the house through underground ducts that exchange heat with the soil. This preheats fresh air to a temperature above 5°C (41°F), even on cold winter days.

- Highly efficient heat recovery from exhaust air using an air-to-air heat exchanger: Most of the perceptible heat in the exhaust air is transferred to the incoming fresh air (heat recovery rate over 80%).

- Hot water supply using regenerative energy sources: Solar collectors or heat pumps provide energy for hot water.

- Energy-saving household appliances: Low energy refrigerators, stoves, freezers, lamps, washers, dryers, etc. are indispensable in a passive house.

(via the Passive House Inst.)

Building Passive Homes inevitably costs more than the typical new home in Japan. However, they are certainly cost-effective if operating costs are taken into account over 20 years or more. Buyers (and more importantly their mortgage lenders) must adopt a long-term outlook when building a new home. Proper shading and passive ventilation are also important for passive homes in Japan’s warmer and more humid climate. Changing planning practices could also help to promote building owners’ access to sunlight (inevitably reducing density). Finally, convincing Japanese to live in passive homes will take a widespread shift in understanding about how energy must be conserved within the home. I am not the first (nor I expect, last) foreigner to complain about Japan’s cold houses, but as an architect, there is something we can do about it. We’re looking forward to building some of Japan’s first passive homes.

One response to “Heating Japanese Homes”

[…] of the term in Japan. The homes were built to encompass three themes: environmental performance (insulation, air tightness, orientation, shading, glazing, natural ventilation, etc); use of renewable energy […]